With a Nod to the Late Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

With a Nod to the Late Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Essay by Drew Koch, CEO, Gardner Institute

December 18, 2023

This fall, the Gardner Institute’s Board of Directors, members of the Institute’s senior leadership team, and guests visited the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Park including Dr. King’s birth home and the nearby Ebenezer Baptist Church. The visits were a part of the Gardner Institute’s annual Board of Directors meeting. As is our custom with that meeting, we made a legal obligation an opportunity for deeper mission-related education, reflection, and inspiration.

The trip served as the impetus for me to reread some of Dr. King’s writings. I was drawn to revisit Dr. King’s 1967 book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

In this book, Dr. King summarized his shift in focus during what turned out to be the last years of his life. Specifically, he ardently made the case that the United States was obligated to alter its approach to helping those disadvantaged by socioeconomic conditions they did not create or control. Further, Dr. King reasoned that since poverty knew no racial boundaries, he could not and would not limit his call exclusively to Black Americans. King noted,

In the treatment of poverty nationally, one fact stands out: There are twice as many white poor as Negro poor in the United States. Therefore I will not dwell on the experiences of poverty that derive from racial discrimination but will discuss the poverty that affects white and Negro alike.

Reading these passages compelled me to examine current demographic data. Reflecting on twentieth-century economic growth in the United States in a 2000 analysis, the University of California Berkley economist, J. Bradford DeLong, noted that, “No previous era and no previous economy has seen material wealth and productive potential grow at such a pace.” Reasonable people would logically conclude that unprecedented wealth expansion in the United States during the twentieth century would lead to some amelioration of poverty.

But they would be wrong.

Very wrong.

According to 2022 U.S Census Bureau data, in many ways, poverty in the United States is as dire and rampant today – if not worse– as it was in the late 1960s when Dr. King wrote his last book. And as in the 1960s, poverty today knows no racial boundaries.

To be clear, persons of color in the United States are more likely to experience poverty than their White counterparts. Race absolutely matters. So does poverty. And as the content that follows supports, poverty affects everyone.

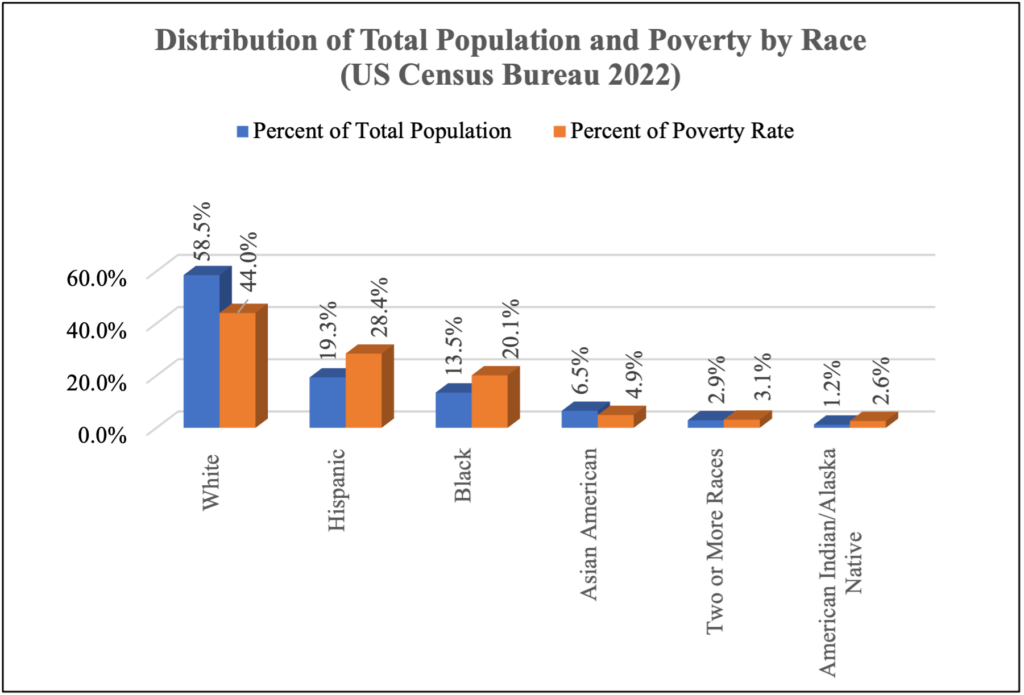

The bar graph below makes these points clear. The graph draws on data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2022 population estimates as well as a recent report released by the Census Bureau on the 2022 Official Poverty Rate.

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that the overall U.S. population in 2022 totaled 333,287,557 people. The Census Bureau also reports that in 2022 11.5% of that population – more than 38,300,000 people – lived below the poverty line. For context, those 38+ million people add up to 4 million more persons than the 2022 populations of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia combined. It’s a lot.

The graph shows that persons who identified their race as White to the Census Bureau account for 58.5% of the overall population (blue bar) and simultaneously account for 44% of the people living below the poverty line (orange bar). This means that White individuals constitute a smaller percentage of the persons living in poverty compared to the overall demographic makeup of the nation. The same trend is present for Asian Americans, who make up 6.5% of the population and 4.8% of the persons living below the poverty line.

On the flip side, persons identifying as Hispanic, Black, Two-or-More Races, or American Indian / Alaska Native are overrepresented in the portion of the U.S. population living below the poverty line. For example, the graph shows that Black individuals made up 20.1% of the population in poverty in 2022 (orange bar) but only 13.5% of the total population (blue bar).

Even with the racial disparities, I believe if Dr. King were alive and writing his book today, he would note that there are now more than twice as many White people as Black people living below the poverty-line in the United States. He’d also need to note that poverty is not only a Black and White issue. Poverty affects persons of all races in the modern United States – and thus it affects all of the United States today.

In his 1967 book, Dr. King called on the federal government to establish a guaranteed middle-class income as a means for ending poverty. Given the divided state of our current government, such a national approach seems far from feasible. But there are approaches that can be undertaken even if Congress is too divided to act. And postsecondary educators have the power and means to take a significant form of action now.

This is because postsecondary education in many forms – degrees, certificates, etc. – is an important means to achieving the desirable end to poverty. A recent report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and Workforce (CEW) makes this clear. That report shares:

The US economy is bifurcated between a large but sluggish blue-collar and skilled-trades economy and a smaller but faster-growing managerial and professional economy. This is leading to a widening economic divide between those who have postsecondary education and those who do not. Postsecondary education or training has become the threshold requirement for access to the managerial and professional economy and the middle-class status and earnings that flow from those jobs during both good and bad economic times. Postsecondary education is no longer just the preferred pathway to middle-class jobs—it is, increasingly, the only pathway.

There are some who criticize the latest CEW report for overemphasizing “the college premium.” These critics have valid points. That shared, even in the current artificial intelligence-shaped era, I believe that more education is better than less education. Humans must and can excel at things that machines cannot do. And I believe those with postsecondary education in its many forms will continue to thrive in the economy of the foreseeable future.

This is the reason I emphasized the last sentence in the CEW report excerpt. If federal action cannot guarantee middle-class incomes for all, postsecondary education can be a key tool to help achieve this desired goal. It should not be the sole tool. But it is an important one.

To make this possible, postsecondary leaders have to acknowledge that their institutions have not been designed to guarantee that all students can graduate. To be clear, my use of the phrase “can graduate” does not mean that I am advocating for diminishing quality or standards and dishing out degrees or credentials the very moment students walk in the door. Rather, my colleagues and I are calling for institutions to take a long hard look at themselves and ask why their respective degree programs are intentionally designed to deny entrance to a major for hundreds if not thousands of students the institution admits into “pre majors?” If institutions are focused on helping students master content, why must one-third of students always earn an F in calculus or other courses as is the case when institutions make use of curve grading? Why do some programs of study have so much structural complexity that students are essentially required to attend more than four years to complete them? (Thereby guaranteeing that some students run out of time and/or need-based aid.) I could go on. I won’t. For now, at least . . .

I am convinced that postsecondary institutions and educators of all types have the means to combat socioeconomic inequality by examining the structures they control and transforming their educational environment so that every student can graduate – not just the select few who come from families with the financial means needed to weather twists and turns.

This may seem like an audacious goal. It is. it is also achievable. In the middle of the third decade of the twenty-first century, we have the means and knowledge to construct better postsecondary experiences; and to redesign and transform higher education in the United States so every student can graduate. The question is not about whether this is possible. The question is whether we have the will.

As a recent Inside Higher Ed article details, there are 11 institutions working with the Gardner Institute that clearly have the will. You can learn more about them in this newsletter. I’ll share more about their efforts – and the efforts of other institutions in cohorts to come – in future editions of this newsletter.

I packed a lot into my inaugural essay for this, our first newsletter. Having done so, I can (and will) sum up the essay’s content in a few points.

As Dr. King wrote in 1967, “The curse of poverty has no justification in our age.” What was true in 1967 is still true now. What is also true is that our nation’s poverty crisis remains as bad today as it was over 55 years ago when Dr. King wrote his last book. This crisis affects tens of millions of Americans from all races and ethnicity groups.

What is also clear is that the completion of many forms of postsecondary education is directly tied to the elimination of poverty and the realization of the American dream. In short, transformation is the key to tackling performance gaps and improving community well-being at the same time.

Institutions must transform so that all students can graduate and become productive members of our democratic republic and its workforce. This kind of transformation will take long-term commitments – you do not change cultures and structures like you change your shoes. This change must occur – for the well-being of learners, institutions, and the broader communities of which they are a part.

The question is not whether you should act.

The question is what will you do so that every student can graduate, so that demographics are not destiny, and so that more of your students can earn family-sustaining incomes and meaningfully engage in society?

You don’t have to join Gardner Institute’s efforts to answer these questions.

But you do have to act.

It is where we all must go from here.

What will you do?